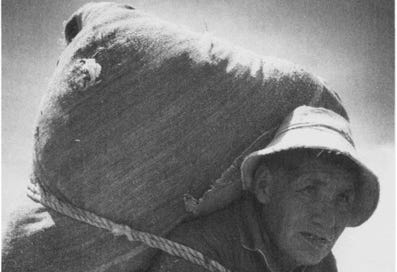

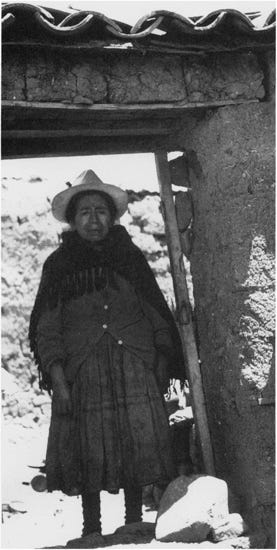

Andean Lives is a testimony translated from Quechua to Spanish to English written by two young anthropologists, Ricardo Valderrama and Carmen Escalante, in collaboration with Asunta Quispe Huamán and her late husband Gregorio Condori Mamani. They were neighbors, lived in a shanty town in the outskirts of Cuzco, when the four encourntered. The biography of two monolingual Quechua speaking runa (peasants) was published in the mid-1970s as a narrative recording the experiences of sever poverty and brutal living conditions in the Andes. Sectioned in two parts starting with Gregorio’s story (3/4 ths) and ending with Asunta’s story (1/4th), the requested intention of this documental novel is “that the suffering of our people be made known” (Post Script).

This book is extremely important, serving a neglected identity by retaining their words on paper, which would have otherwise been taken by the wind (Post Script). I don’t question the important of documenting stories. I often sink at the thought of stories or complete knowledge systems which have been lost, imagining which misunderstanding could be corrected and made compassionate, had we had direct access to impacted voices. From reading Andean Lives, mixed with my sense of tragedy and devastation is a feeling of awe and gratitude that the stories have survived and disseminated, as a type of socio-history often aired over and unattended.

In an essay from 1977 published in Centro de Estudios Rurales Andions, Javier Zorrilla E describes this biography as “Mitos ancestrals que se encarnan en el hombre concreto, en Gregorio, y reinterpretan la historia” (Ancestral myths that are incarnated in the concrete man, in Gregorio, and they reinterpret history). In this, chapters which explain ayni (labour exchange and cooperation), laymi (communal sectoral farming systems), Chakrakamayuq (fieldmaster who determines planting scheduled via ritual and knowledge of climactic phenomenon) are likely what is referenced to as ancestral myth involved in Andean history, though a darker and directly colonial aspect of ancestral stories mostly conducts the Asunta and Gregorio’s lives.

The incarnation of Asunta and Gregorio’s stories are not definitively universal to Andean experience, though Asunta’s view of life suggests a devastating norm:

“But so it is –with all the sin that exists in the world, to live this life is to suffer. Yet, everybody from the tiniest moth to the mountain lord’s fearsome puma, from the largest tree to the smallest blade of grass spreading without a thought, all of us here since those distant time of our ancient ancestors, we’re all just passing through this life…”

“But our soul, our spirit, doesn’t disappear. It’s the same with the souls of the ancient ones and with those of our family members and friends—they haven’t disappeared; they’re living in the other life, in either the underworld or upper-world. There you have everything you need, and you can rest from these sufferings and this life of tears” (Ch.15: I Stopped Bearing that Cross)

Asunta describes a Christian notion of faith, likely instilled from her early years working on the priests’ hacienda, hybridized with the three world Incan cosmovision (Ukhu Pacha/under-world, Kay Pacha/earth-world, Hanan Pacha/upper-world). Abuse, servitude, emotional and physical ailment comprise the suffering Asunta is accepting and resiliently adapting to within the earthly-plane.

Reflecting on the experiences of the pair within their own relationship, within the abusive constellation of family, struggling from displacement from their own ‘unregistered’ land, and unsafe exploitative labour dynamics*, appearing are cycles of trauma that deprive dignity from people who’ve begun to only rely on the salvation of judgement day. Long story short, the violence endured and reproduced is indeed induced by the colonial project. *on labour dynamics:

“The life I led in that mine was one big lie—you’d work month after month, but your full wages never showed up. If you worked two months, they’d just pay you for one. So when people wanted to quit and leave the mine, they’d always have to wait around for their wages. They’d keep on working, but they’d still never receive their full pay and would have to leave behind two or three months of unpaid work.” *

Daily wage being 3.20soles does not measure to the brutal working conditions, which Asunta sympathetically notes to have contributed to the rage and mistreatment endured at home (by husband Eusebio).

Other themes of jealousy and betrayal in this testimony show that this era in the Andes did not attract orders in kindness and reciprocity nostalgically known before colonial-feudal-bureaucracy arrived and augmented unfair suffering of Indigenous populations.

Past are the toil of your bodies, may your souls rest in peace

Asunta Quispe Huamán

Gregorio Condori Mamani

And may the lineage lead by Asunta’s only living child,

Catalina

be resilient to carry forward into lighter conditions of a wrongly effected peoples.

x

Hi Emma,

I loved what you said here "From reading Andean Lives, mixed with my sense of tragedy and devastation is a feeling of awe and gratitude that the stories have survived and disseminated, as a type of socio-history often aired over and unattended."

I really wish that Andean lives had included more about Asunta's life, the intersection of gender and Indigeneity was very prevalent in the content split. I too feel grief for stories lost, pretty much anytime I read a true account. I am curious what has been left out/edited out of Asunta's account simply because of its length, or if maybe that was all she wanted to share?

Life is hard enough without the overlay of injustice